Quando tirei o curso tive um professor que anda ía pelas ruas da amargura e é conhecido como o marido da Bárbara, Manuel Mª Carrilho. Devo já dizer que foi um bom professor. Ele dava uma cadeira de epistemologia do 3º ano. Logo na primeira aula, disse-nos, 'espero que não tenham vindo tirar um curso de filosofia para dar aulas, seja aqui na universidade ou noutro sítio qualquer. Pode-se ir dar aulas com este curso mas não se deve tirar este curso para ir dar aulas. Usem o curso para filosofar, para pensar, para mudar o mundo. Pensar é um risco. Arrisquem' Esse foi um conselho que ficou comigo e agora lembrei-me dele a ler este artigo acerca da vida académica actual que não induz o pensar e que produz muita banalidade.

Academia, a theater of “grinding competition and relentless banality,” is no longer a place to live the contemplative life...

Intellectual life is impractical, at least when set against the narrow confines of academic life.

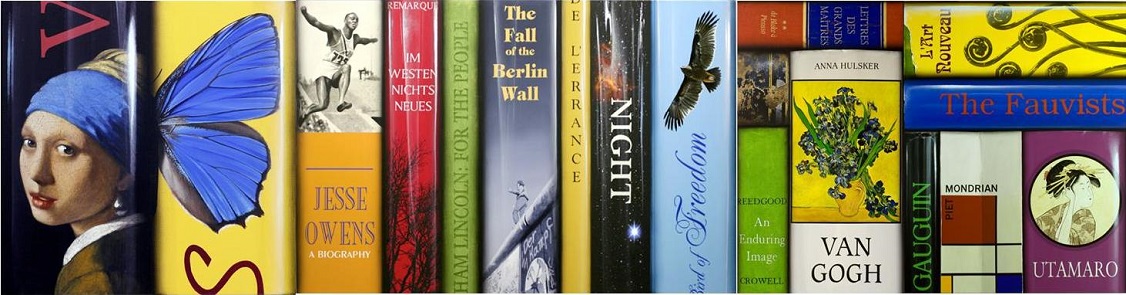

What Hitz found in the historical figures she surveys is a love of learning for its own sake and an openness to the transformative potential of thought, qualities that define her own attitude toward education (and serve as a foil to the obsession with competition and “knowledge production” that characterizes modern academe). “When I read Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels,” she writes, “and their account of the lifelong friendship between two women from girlhood, I recognize features from my own friendships with other women.” One gets the impression that in Du Bois and Day, Hitz sees individuals who, like her, discovered the world-expanding power of books, which can serve as a hidden passageway leading from the perilous world to a rare and precious truth.(...)

Unlike Hitz, though, for me philosophy has never served as a source of worldly comfort. This has also been the case for many people I’ve befriended over the years: The contemplative life hits us as a kind of sudden derangement, ripping us out of the fabric of life, driving us into libraries, bookstores, and campus events in desperate efforts to meet fellow travelers. But when we get there, we find that our eccentricity, roughness, and lack of training in academic gentility make such relationships impossible. Letters go unanswered, invitations withheld, applications rejected. For every Socrates — calm and satisfied, capable of coaxing the good out of others — how many more are like Alcibiades in Plato’s Symposium, bitten by the viper of philosophy and left struggling to soothe its sting?

by

Joseph Keegin

No comments:

Post a Comment